Searching for Beauty in the Season of Grey

Style? Technique? Subject matter? Soul power? What exactly IS “beauty?”

According to Webster’s Dictionary [the authority before Google], beauty is “that quality or aggregate of qualities which gives pleasure to the sense or pleasurably exalts the mind or spirit; physical, moral or spiritual loveliness.” Artists may search for it in nature or within themselves, but any exhibit of art reveals widely differing concepts and approaches.

My house, gallery and studio are covered with paintings, a veritable museum of all the attempts to recapture some aspect of God’s world. Naturally style, technique and subject matter morphed as my ideas of beauty evolved over the years but mostly stayed true to natural coloration. When did beauty reject her brilliant silken garments to don grave clothes?

Beauty began seriously losing ground over a hundred years ago with various manifestos by artists and groups who detested the work and practices of the French Academy. Their determination was to change the whole concept of artistic freedom, religion, family, government and what have you. Art for Art’s sake was the rallying cry for anything goes. The glorification of art, as opposed to divinity, became the new norm.

Realism, or even reality itself, hasn’t been favored much in academia since the 1930’s or in the rarified echelons of New York critics. Certainly not Christian art. Culturally speaking, God’s art simply became less relevant as the Renaissance progressed onto a more scientifically oriented basis. The Protestant reformation further muddied the waters. That is your shortened version of a very complex subject. You can read more if I ever finish my book.

Beauty can take on a different role—consolation, a lesser known aspect of beauty. Carol, a veterinary assistant and talented pencil artist, took my workshops for several years. This is her story:

“Some time ago, I was to be given a Mustang-Quarter horse cross in a trade. There were two horses to choose from. It should have been a no brainer. One had been neglected as a pasture horse, picked on by the other horses who kept her from food and water, so this filly was about 75 pounds underweight. Walking into the pasture, I felt attracted to the beautiful Paint mare, the obvious choice.

Instead, I trailered home the bony, cow-hocked 8-month old bay who walked up to me, laid her head on my shoulder and hugged me, all but saying out loud, ‘Take me home.’”

She continued, “Briscoe will never make a show horse, but she has become beautiful to me. I love her personality and intelligence. I really didn’t want her, but I needed her. She’s good for my soul.”

Sometimes love figures in the equation of beauty. When my soul turns grey, I turn to my library of the great Masters. I read Robert J. Clements’ Michelangelo’s Theory of Art. After seeing Michelangelo’s sculptures in the Academy at Florence, Italy, particularly the David, it was love at first sight. Spoiled by the real thing, my life is devoted to finding how to use paint as an avenue to unchain beauty from her bonds. True beauty appears effortless, as if it created itself.

The work of Michelangelo transcends mere versatility. This giant of the High Renaissance was greatly influenced in early manhood by the words of the fiery monk, Savonarola, who stated that “only the most distinguished masters should paint [for the churches] and should paint only noble things.” Michelangelo spent his life in search of the sublime, a task akin to the quest for the Holy Grail. He died without believing he had found it. Instead he left it for us to find.

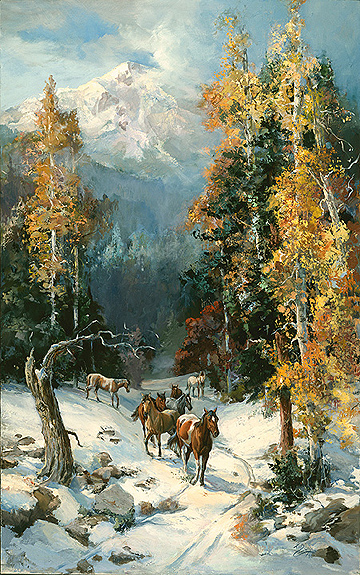

Beauty invites the search for nobility through color and form. I believe that artists must strive for the same breakthroughs, the wee touch of heaven. While not fashionable to speak of sublimity or divinity, they were once taken for granted. We are indeed blessed by our association with the equine form, enabling us to touch what is beyond ourselves, a reminder that the union of man and horse is greater than the sum of the parts.

Comments are closed.